Malcolm Dixon on the Department

At the Jubilee celebrations in 1974 Professor Malcolm Dixon summarised the history of the area surrounding the Downing Site from long before the Physiological Laboratory came into existence. He noted that in the fifteenth century Downing Street was known as Landgrythes Lane and that the first stretch from Trumpington Street follows the line of the King's Ditch that was the outer defence of the town of Cambridge. The address of the Department (Tennis Court Road) has its origins in a private lane from Downing Street to the real tennis court building that from 1565 until the early years of the nineteenth century was situated near the present position of the back gate of Pembroke College. The Downing Site itself was originally called Swinecroft after the Swyn family, or St. Thomas' Leys after St. Thomas' Hostel next to Pembroke.

Dixon went on to remind everyone that 50 years before the Hopkins Building was constructed the University had no laboratories. A few Colleges had their own laboratories in the period when they, the Colleges, taught science rather than the University. The mahogany bench of the main lecture theatre was a relic of this period, rescued by Hopkins from the St. John's College laboratory. The New Museums Site was originally the grounds of an Augustinian Friary (occupying the area from Bene't Street to Downing Street and from Free School Lane to Corn Exchange Street). When the friary dissolved it was bought by the Vice-Master of Trinity, for £1,600 in 1760, and was given to the University as its Botanical Garden. This became the site for two or three houses for Professors of Science to keep their own collections of specimens and apparatus and to give lectures, which thus became the 'New Museums'. The removal of the Botanical Gardens to their present site provided space for laboratories including, in 1876, for Physiology and Comparative Anatomy adjacent to Corn Exchange Street where the David Attenborough Building now stands today. In 1914 this became the first home of the Department of Biochemistry.

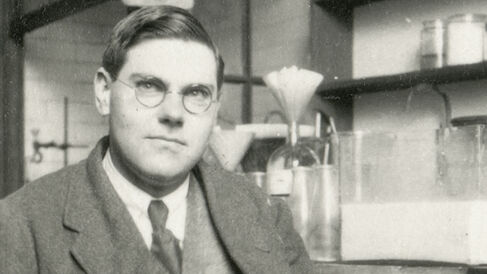

Malcolm Dixon was born in 1899 and, as a local boy, he went to the Perse School in Free School Lane. This was the 'Free School' established by Dr Stephen Perse in the seventeenth century, the original school hall of which now houses the Whipple Museum of the History of Science. It was in the year of his birth that the University bought the northern half of the Downing Site. This was sold by the Downing trustees because, having bought all the land between Downing Street and Lensfield Road to build a College of great magnificence, they discovered that they had insufficient funds. The plan was to build laboratories on that land to relieve growing congestion on the New Museums Site. There was much opposition to the scheme, however, because it was held to be inconceivable that science could ever need that much space and that, in any case, no one would wish to use a site so far from the town.

After the Department outgrew its space in Corn Exchange Street, at which Elsie Bulley would arrive on horse-back, it moved in 1919 to the Balfour Laboratory in Downing Place in what later became the Music School (now known as the Old Music School and current home of the Language Centre). This had been built in 1790 as a non-conformist chapel before, in 1884, it was opened as the Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women for the benefit of students of Newnham and Girton Colleges taking the Natural Sciences Tripos. Biochemistry shared this laboratory for four years before the Department had to move out in 1923, which caused some difficulties because the new building (the Sir William Dunn Institute of Biochemistry, now known as the Hopkins Building) was not completed for its official opening until 1924. That might have been even later, as it emerged when construction was well under way that the building was in the wrong place, being some fifteen feet north of its allocated site. The view was taken that it was too late to move it but a consequence of the mistake can be seen to this day in the form of the right angle bend at the Pembroke end of what is now the Department of Genetics.

Malcolm Dixon observed that the design of the Hopkins Building reflected the science of the time. As you could not then buy biochemicals you had to make them, so there were hot rooms for running tryptic digests but no cold rooms. As for equipment, there were incubators but no refrigerators; ice was acquired in large blocks from the fishmonger.

Reminiscing about the Hopkins Building, Malcolm Dixon referred to John Steegman's book on Cambridge architecture, the author's comments on the Downing Site in general and on the Biochemistry building in particular, "This extraordinarily depressing area is one of the most intense concentrations of scientific knowledge in England… But nobody would imagine, if he did not already know, that these meaningless shapes are really laboratories and museums which draw students and scholars from over the whole world. They might be banking houses or the dwellings of Edwardian millionaires or liberal clubs… There are, however, one or two of these institutions which do not actually hurt the critical spectator. The Institute of Biochemistry in Tennis Court Road, designed by Sir Edwin Cooper in 1923, is exceedingly stylish, though what style it is supposed to be is not certain, nor can one be certain when looking at the outside as to what function this very self-conscious pink-and-white edifice is intended to perform." To which Dixon added "This was before we stuck the new wing [the Wellcome Wing] on the back."