Image: On the front row of this 1930 Department photograph, Frederick Gowland Hopkins is sitting in the middle, Dorothy Needham is second from the left and Marjory Stephenson is second from the right.

Dr Stella Butler, Librarian Emeritus University of Leeds, Honorary Fellow University College London.

In March 1945, just as the Second World War was coming to a close, the Cambridge biochemist, Marjory Stephenson became one of the first two women to be elected Fellow of the Royal Society. Three years later, in Spring 1948, her colleague at the Dunn Institute of Biochemistry, Dorothy Moyle Needham, also joined the ranks of this most distinguished of scientific academies.

Both women had been working in the Cambridge laboratory of the Nobel Laureate, Frederick Gowland Hopkins since the early 1920s. Marjory had become well known for establishing a sub-discipline of biochemistry with her seminal textbook, Bacterial Metabolism, published in 1930. Working with her student, Leonard Stickland, on bacteria harvested from the River Ouse near a sugar beet factory, she had discovered the enzyme responsible for producing the gas, hydrogen sulphide, with its distinctive odour of bad eggs. Dorothy Moyle Needham’s reputation rested on her meticulous experiments on the chemical reactions that occur within muscle cells. By the early 1940s, she had elucidated much of the pathway through which glucose is broken down to produce the ‘energy currency’ chemical, adenosine triphosphate. The research of both women contributed fundamental knowledge about the chemical reactions essential to the life of all organisms.

Both Marjory and Dorothy had studied as undergraduates at Cambridge: Marjory Stephenson at Newnham College between 1903 and 1906 and Dorothy Moyle at Girton between 1915 and 1919. Both went on to achieve doctorates. But neither were able to receive more than the ‘title’ to their degrees as, until 1948, women were not eligible to become members of the University of Cambridge. Rather than graduate in cap and gown, both Marjory and Dorothy simply received a letter, informing them of their examination success.

Image: Dorothy Needham at her laboratory bench in the 1920s.

Although women were not formally members of the university, there was, nevertheless, a warm welcome at the Cambridge biochemistry laboratory. Hopkins gave Marjory, Dorothy and a host of talented women scientists every encouragement to develop the knowledge and experimental skills which were becoming the bedrock of the new discipline of biochemistry. Hopkins was an inspirational leader attracting some of the brightest brains of the 1920s and 30s. There was a vibrant intellectual atmosphere within the department: at the weekly tea club meetings, Marjory and Dorothy enjoyed discussions with colleagues including Joseph Needham, J.B.S. Haldane and Malcolm Dixon. The place buzzed with energy and ideas. Romance also regularly blossomed including between Dorothy Moyle and Joseph Needham who married in 1924.

Women scientists in this period often struggled to secure permanent appointments either in universities or in the private sector. Both Marjory and Dorothy spent much of their careers on ‘soft money’. Initially, Marjory Stephenson’s research was funded through a Beit Memorial Fellowship. When that came to an end Hopkins arranged annual grants from the Medical Research Council until, in 1929, she was given a permanent contract with the MRC.

Image: This illustration is taken from Marjory Stephenson’s article, ‘Down the microscope and what Alice found there’ in the department’s humorous Brighter Biochemistry journal, 1927.

Dorothy began her career with a grant from the government’s Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. Unlike Marjory, Dorothy never received or even applied for a permanent post. In the 1980s, she recalled, somewhat wistfully, that she, and other married women of her generation, had been expected to be supported financially by their husbands “and, if they chose to work in the laboratory all day and half the night, it was their own concern”. On at least two occasions, her married status made her ineligible even for grant funding.

Image: Staff at the Dunn Institute for Biochemistry 1943: Malcolm Dixon, Dorothy Needham, Robin Hill, Ernest Baldwin, A.C. Chibnall, Marjory Stephenson and David Bell

1945 was a turning point for the Royal Society. The election of the first two women Fellows, the crystallographer, Kathleen Lonsdale and Marjory Stephenson, involved considerable behind-the-scenes machinations by the President, Sir Henry Dale, and his allies. Marjory Stephenson was so fearful of the likely publicity the announcement of her FRS would receive, she fled Cambridge for the countryside! In the event, she need not have worried, there were, it seemed, bigger stories elsewhere and the election of Lonsdale and Stephenson was barely acknowledged by the press.

Marjory Stephenson was already seriously ill when she became FRS. Breast cancer had been diagnosed in 1944. She did return to work after surgery but never regained full strength. In 1947, she was appointed Reader in Chemical Microbiology by the University of Cambridge. However, by then, secondary tumours had developed and she was unable to enjoy fully the plaudits her scientific achievements received. She died in December 1948.

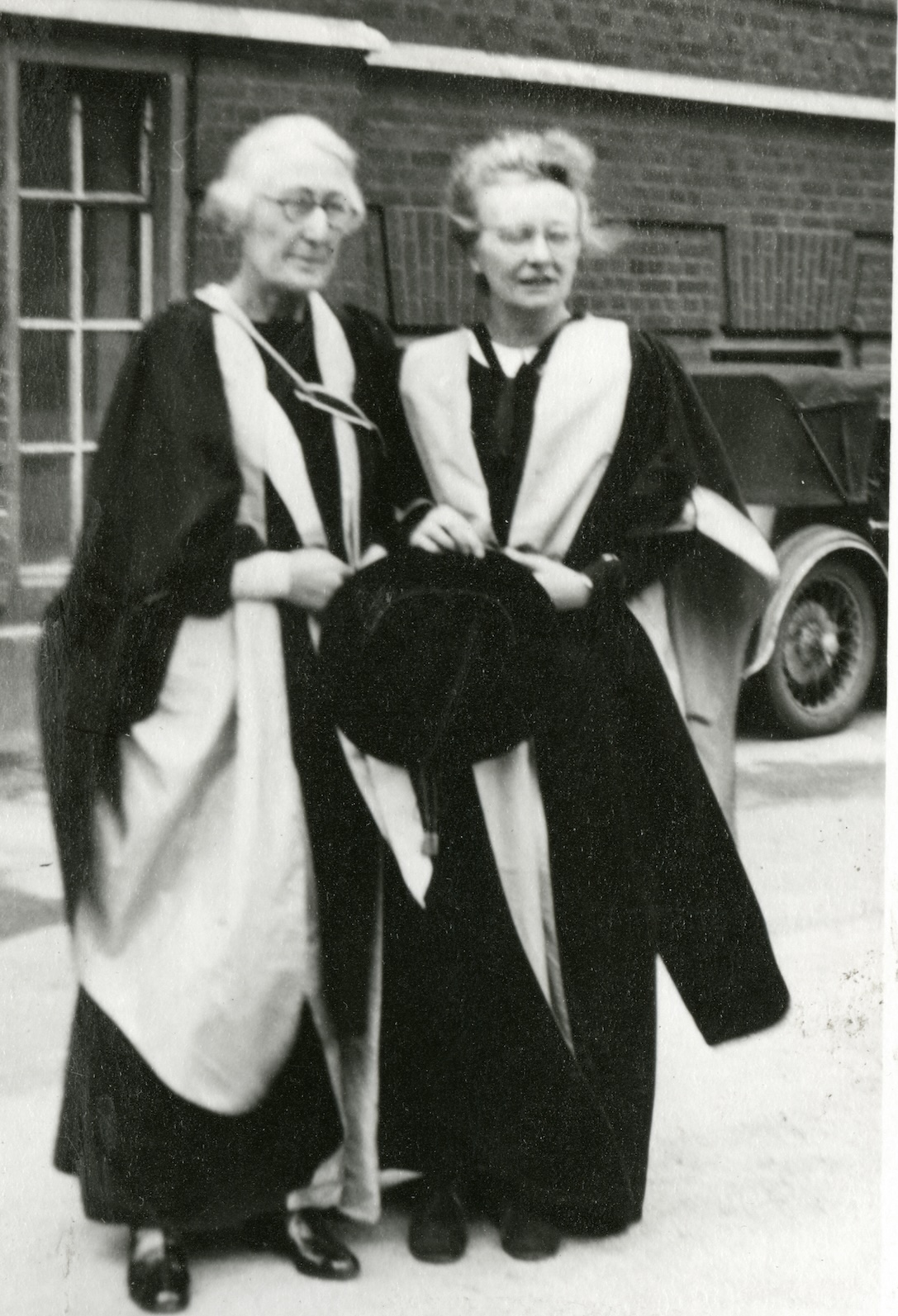

Image: Marjory Stephenson and Dorothy Needham attending the installation of Jan Smuts as Chancellor of the University of Cambridge in 1948

When Dorothy Moyle Needham became FRS in 1948, she had settled back into life within the Cambridge Biochemistry Department, having spent the last year of the Second World War working with her husband, Joseph, in China. During the 1950s, she continued to research the biochemistry of contracting muscles. After retiring from experimental work, in the 1960s, she devoted herself to writing a definitive account of the history of muscular contraction, Machina carnis, which was published in 1971. She became Honorary Fellow of three Cambridge Colleges: Lucy Cavendish, Girton and Caius. The latter recognised her contribution to Caius between 1966 and 1976, while Joseph Needham was Master. By the 1980s, Dorothy was beginning to exhibit the early signs of Alzheimer’s disease. However, she continued researching and writing on the history of biochemistry until her death in December 1987.

Marjory Stephenson and Dorothy Needham were outstanding scientists, both pioneering new avenues of research and shaping ideas about the chemistry of life. Both played central roles within the Dunn Institute for Biochemistry and the wider Cambridge academic community. Despite their academic distinction, both women struggled to achieve financial security and institutional recognition. However, by becoming Fellows of the Royal Society, they demonstrated that women could be accepted into the upper echelons of science. Equality with men was still a long way off. But their elections represented a significant step in that direction.

Stella Butler’s book, Breaking the Glass Ceiling of Science: the first eleven women to become Fellows of the Royal Society 1945-1954 will be published by the History Press later this year.