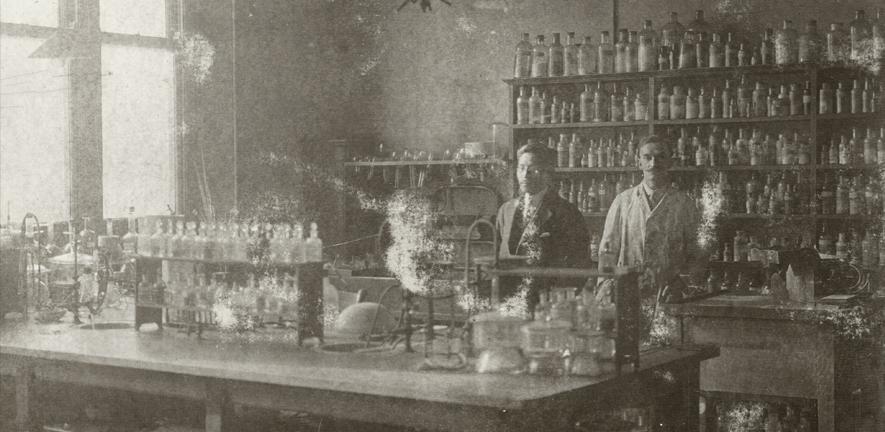

When the war ended the numbers working in the laboratory on Corn Exchange Street (the site where the David Attenborough Building is now located) rose quite rapidly. One of the first new recruits, in 1918, was also one of the most remarkable. Whilst still a student taking Part II Physiology, Rudolph Peters had showed that in oxyhaemoglobin one molecule of labile oxygen is united with one atom of iron. When war broke out, Peters completed his degree in medicine at St. Bartholomew's Hospital and became the Medical Officer in the 60th Rifles. He served with them at Delville Wood, Vimy Ridge and Beaumont Hamel, winning a Military Cross and bar and being mentioned in dispatches. Peters was recalled from the front in 1917 to work at Porton Down on chemical warfare. Among other things, he showed that small amounts of thallium salts in the medium of Paramecium made the ciliate protozoa reverse their ciliary action, prompting a visiting General to exclaim "What! A gas that makes the enemy go backwards!" In the 1929 Harben Lecture, Peters said "The fact that the cell contents are often quite fluid can be reconciled with the fact that the living cell shows a continuous directive power by the view that protein surfaces in the cell constitute a mosaic form which radiate chains of molecules, controlled by their attachment to the central mosaic. These constitute a fluid anatomy in the cell, and the central mosaic behaves as a kind of central nervous system."

With Frederick Gowland Hopkins, Peters carried out early pioneering work on vitamins. From 1923 to 1954 Peters was Whitney Professor of Biochemistry at Oxford, after which he returned to Cambridge. During the Second World War Peters developed an antidote to the gas Lewisite, and, in 1964, he showed that fluoracetate, which had been produced as a commercial insecticide, was toxic, eventually persuading the Ministry of Agriculture to ban it.

The period immediately following the First World War also saw the New Zealander Huia Onslow, whose father had been Governor of New Zealand, working on pigmentation and Muriel Wheldale establishing the field of plant biochemistry, working particularly on chloroplasts. In 1919, Onslow and Wheldale became husband and wife - the first, but by no means the last, intra-Departmental marriage. Onslow had been paralysed in a diving accident, but despite this ran a research programme in chemical genetics from a laboratory constructed in his own home.

With the Department outgrowing its space in Corn Exchange Street, it moved in 1919 to the Balfour Laboratory in Downing Place in what later became the Music School (now known as the Old Music School and current home of the Language Centre). This had been built in 1790 as a non-conformist chapel before, in 1884, it was opened as the Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women for the benefit of students of Newnham and Girton Colleges taking the Natural Sciences Tripos. Biochemistry shared this laboratory for four years before the Department had to move out in 1923, which caused some difficulties because the new building (the Sir William Dunn Institute of Biochemistry, now known as the Hopkins Building) was not completed for its official opening until 1924.